Step 5:

Decide how to convey messages

A. How to focus on changing the narrative for the general public:

People’s reactions to communications about prisons are guided by a set of strong beliefs about why people commit crime and how to reduce crime. These beliefs affect everyone, are deep seated, strong, and sometimes contradictory. We are unlikely to fundamentally change people’s beliefs, but we can change their appetite for progressive reforms by triggering some beliefs and moving the debate to a more inclusive narrative.

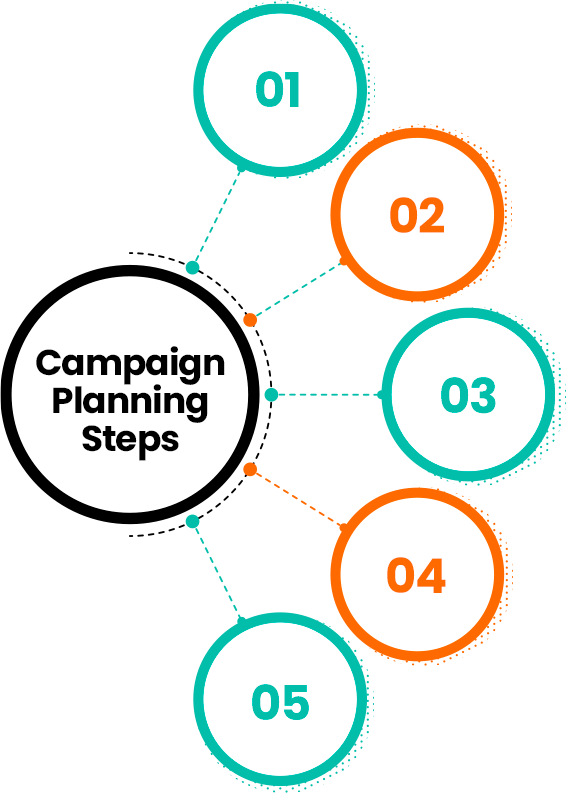

Narrative Change Campaign

Find a focus and opening

Develop a campaign strategy that identifies a target segment, the value appeal you will work with and an event or debate to target.

Build out the elements

Develop messages, stories, evidence and visuals. Select messengers and decide on the tools and resourced needed. Put togheter the nuts and bolts of the campaign.

Prepare for responses

Test your messages, develop talking points and preparethe team for challenging exchanges.

Run the campaign

Get ready to go! Plan the sequencing and monitoring. Roll out the campaign and expect the unexpected!

Evaluate reach and uptake

Asses how well you reached and engaged/convinced your target audience with your new narratives.

Frames and messages you would rather avoid

Crime is an individual, rational choice: The belief that those who commit crime are “rational actors” is powerful. People think that crime is committed by those who logically weigh up the chances of being caught, and the punishment that would follow, against the potential benefit of committing the crime.

Deterrence: If you believe people decide whether to commit crime by considering the punishment that would be meted out to them if caught, you are also likely to believe in deterrence. People think that the prospect of punishment prevents people from committing crimes, and from reoffending. Triggering people’s faith in deterrence will lead them to call for harsher and more “consistent” punishment, since that would provide a strong incentive against committing crime.

Punishment: Typically most people believe prison exists to punish. That punishment deters crime and that retribution is desirable. This is a strong belief that underpins support for harsher punishment, and for imprisonment. For many, punishment is the primary purpose of the criminal justice system. There are two ways to deal with the belief in punishment.

1.Do not refer to punishment as a goal of the system

2.Tackle the belief head on by explaining why harsh punishment does not reduce crime.

Human nature and moral breakdown: Many people think that some people are just bad, that it is in their nature to commit crime, and that nothing can be done to reform bad people. Some blame moral breakdown for this badness. They think moral standards are declining, and people no longer know right from wrong. Avoid any implication that a propensity to commit crime is innate, genetic or runs in families, and any support for a decline in morality.

Frames and messages you would rather focus on:

Crime has societal causes: People do understand that being poor can lead people into crime, either because they need to steal to survive, or because they are led there by their social upbringing. People also understand that if someone is surrounded by people who commit crime, they are more likely to commit crime. Conversely, if someone has a positive and supportive environment with good role models, they are less likely to commit crime.

Rehabilitation: The public supports rehabilitation as one of the purposes of the criminal justice system. It is not as strong as the beliefs in punishment and deterrence, but can be triggered. Rehabilitation is usually viewed as providing detainees with an education and job skills, to help them rebuild their lives meaningfully and have a second chance on release. Focus on rehabilitation in prison, and the avoidance on recidivism.

Alternatives to prison: These are definitely not top of mind but can be triggered. People can see that, given the conditions in prison, alternatives for those who commit less serious crimes are worth considering. People also understand that those who are imprisoned may learn “bad lessons” from others in prison. This does not mean we should say “those who commit serious crimes should be punished in prison”, but that we should promote alternatives to prison.

B. Create and develop clear messages

Always keep in mind “What is the clear message we want to communicate”?

– What is the main point you want to communicate to your audience?

– Is the language appropriate for your target audience?

– Use clear, straightforward language for advocacy messages.

– Always use language which is familiar to the specific actor being addressed.

– Use the target audience’s terminology and examples, building on their experience.

– Statement (the central idea of the message), Evidence (data to support the narrative), Example (engage the audience), and Action Requested (what has to be done to change the situation).

Sample messages:

“Hope can be born in prison”

“Justice means no revenge but reintegration”

– What is the main point you want to communicate to your audience?

– Use examples of successful cases of individuals, highlighting “… has been convicted himself/herself”, helps to create closeness and overcome the stigma.

– Let employers talk directly about the contribution of ex – convicts in their own business etc.

– Let ex-convicts talk on how much their lives changes through a well-structured process of reintegration.